‘Climate Change is driving 2022 extreme heat and flooding.’

‘Europe swelters in record-breaking June heatwave.’

‘Massive forest fire in California turns 18000-acre jungle to ash.’

Everest’s highest glacier rapidly losing ice.’

‘49 degrees in Delhi, flash floods in some regions. Experts warn of climate change.’

‘Climate change: IPCC report is ‘code red for humanity.’

‘Rain-triggered floods in Bangladesh conjure climate warnings.’

These are just some of the alarming extreme weather events in this year alone that have made it to the headlines. As you read this, Pakistan is reeling from unprecedented rain and flooding that has devastated the country. And we can be sure to expect more such weather events around the world that tells us that climate change is very real and is taking place at a rate not seen in the past 10,000 years.

The current warming up of the planet is seen as result of human activities and the emission of greenhouse gases since the mid-1800s. CO2 is the greatest contributor to the increasing global warming and has risen by 48% when compared to pre-industrial levels. Methane is the second largest contributor and its concentration in the atmosphere has also more than doubled since preindustrial times. The obvious solution to climate change at this point is to immediately reduce energy related emissions, and transition to alternative sources of energy. Activities which include burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas increases the emission of carbon pollution, resulting in climate change. The process of replacing fossil fuels with low carbon and renewable energy sources, called energy transition, should be the topmost priority in gearing up for climate resilience and sustainable development.

The question, however, that remains is whose responsibility is it to do so and who is the burden falling on?

Decades of global commitments

It was only in 1972 that the world started taking the environment and the effects we were having on it seriously with the United Nations Scientific Conference on the Human Environment, more popularly known as the Stockholm Conference. In 1987, climate change and its potentially devastating consequences first made it to the global agenda. With the goal of stabilizing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere ‘at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system’, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was introduced in 1992 and as of today has been ratified by 197 countries. In the time since, there have been many conferences held and agreements and protocols that have been proposed and signed. Key amongst these are the Kyoto Protocol , Paris Agreement and the annual Conference of Parties (COP) that was started to monitor and review the implementations of UNFCCC a and where countries meet annually to discuss goals and objectives related to climate change.

What has India committed to and does it have the capacity to achieve its targets?

Countries, including India, have been voluntarily making commitments and declaring targets for themselves since 2015 in Paris. At the most recent COP in 2021 too, India committed to achieving 5 targets, collectively known as Panachamrit, which are as follows:

- Increase non-fossil energy capacity to 500 gigawatts (GW) by 2030

- 50% of the country’s energy requirements will be from renewable energy by 2030

- Total carbon emissions will be reduced by one billion tonnes from now to 2030

- Reducing carbon intensity of the economy by 45% by 2030 from 2005 levels

- Achieving net zero emissions by 2070

India’s ambitions and targets are commendable and promise a better, sustainable and a much healthier planet for the generations to come. But a looming question, that has not really been answered yet, is how will we actually achieve them? What is or should our action plan be?

Increasing the share of renewable energy and reducing dependence on fossil fuels looks good on paper. As does reducing carbon emissions by 1 billions tonnes. But to be able to do this we need the financial capital as well as a cross-sectoral energy transition plan. Where are the investments coming from? Of the 1 billion tonnes, which energy sector will be responsible for what share of reduction? Simply committing to transition to solar energy will not be enough. Do we have the infrastructure make this transition – do we have the grid system and connectivity for energy movement that would be required to truly move to a renewable source of energy?

The biggest problem in India currently is the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and their contribution to emissions. As things stand today, they have limited knowledge, financial capital, and consequently no drive or motivation to reduce their emissions. However, if we were to focus on just the MSMEs we could see as much as 40% reduction in emissions which will go a long way in achieving Net Zero.

While there is still lack of investments in the energy transition sector, it accounts for a significant share in the input costs (between 10-25% for energy-intensive industries). Within this sector, millions of MSMEs account for 90% of the industrial units, with high energy costs relative to the costs that industries face in other major economies. When purchasing power parity is seen from a global context, India pays five times the power price of that of US’s industry and two and a half times more than that of China’s. With India’s contribution to the global graph as a polluter of carbon emissions, it is shocking how we are paying more than the highest and second highest polluters. This makes a strong case for energy transition. With the MSME sector large enough to consume approximately 30% of energy delivered to formal industrial units, energy transition in this sector will make a significant impact. Mandating energy audits for firms with more than INR 25 crore turnover is necessary and so is mandating disclosure of energy consumption for large companies. This will help the MSMEs to prosper while becoming energy efficient.

Moreover, it is important to understand that energy transition is not just about changing the source of energy. It also entails a whole host of supply chain issues, production issues, different sectoral issues, etc. As of now, India has no mechanism for a central authority to oversee and coordinate all these issues. Let’s take for example the target of reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Who will decide which sectors will make the complete transition and which sectors can continue to depend on fossil fuels? Of those that will transition will need to decide what changes do they need at the policy and technology level that will enable this change? Further, we must also remember that energy is not limited to just the power sector but also to the gas and fuel sector and any long-term transition plan will need to take into account all sources of energy and emissions.

Does India NEED to achieve these targets – whose problem is this really?

Though India has become infamous as the world’s third-highest polluter in carbon emissions, but when compared to that of China and United States of America (USA), its emissions are like a drop in the ocean. China’s carbon emissions are 10.6 gigatonnes (GT) and that of US’s is 5 GT, which cannot be compared, not even close, to that of India’s, 2.88 GT. With a great margin between the first and the second highest polluter in the world, emphasis must also be given to India’s huge population- implying its per capita emissions to be much lower than other major world economies. From 1870 to 2019, India greenhouse gas emissions account for a meagre 4% of the global total.

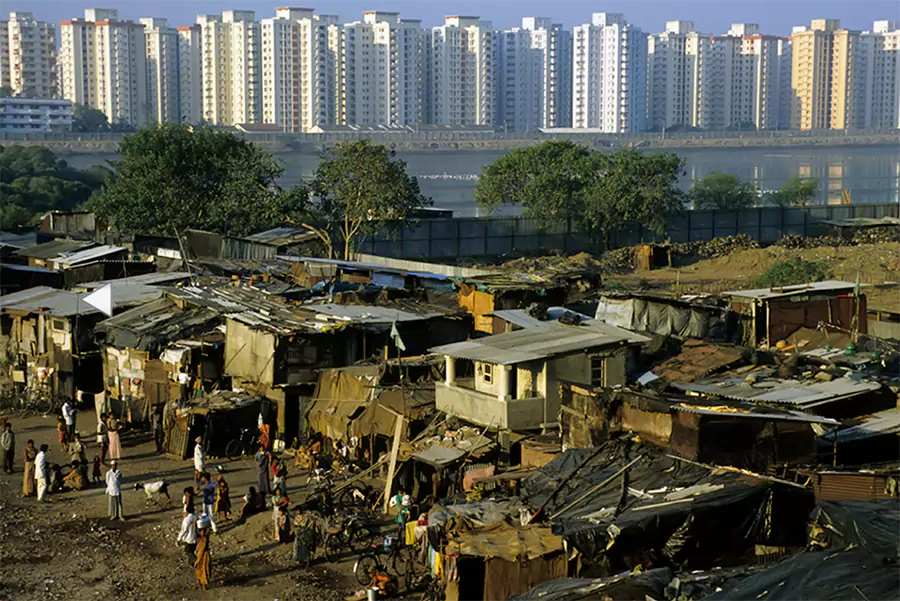

The problem is that the bigger culprits, the countries that have already developed, with emissions that went unchecked, are now putting the burden of those that still have a long way to go in their development journey. More importantly, the adverse consequences of climate are more likely to hit and impact those countries who had little contribution to the emissions in the past and account for a fraction of it even today. Developed countries have better coping mechanisms and therefore can better absorb the shocks of climate change and a warming planet. They have a dual advantage – they were/are the major contributors to emissions and can also deal with the repercussions of that better. Developing countries on the other hand have had a negligible contribution to the changing climate but will be the hardest hit.

It is unfair, and unrealistic, therefore, to expect developing countries such as India to make such significant cuts in their emissions.

The way forward for India

As a developing country with the second largest population and a significantly large gap with the highest and second highest polluter of carbon emissions in the world, India’s emissions are a drop in the ocean. While India has no immediate obligation to reduce its current emissions by a drastic percentage, the imperative should also not be on India. Nonetheless, in the long-term we must transition and do everything we can to combat climate change and the havoc it could wreak on the planet.

Over the decades, through the various agreements, protocols, conventions and conferences, we have done a lot on paper but now it is time to walk the talk. In India, we need to start thinking locally and providing finances to the industries to help them transition. We also need to create synergies. At the moment we are operating in a very adhoc manner, in silos, which no comprehensive way forward. To be able to truly achieve our targets, whether in is the timeframe we have committed to or beyond, we need convergence – we need a central authority that will take charge, that will create a blueprint and chart the next steps. Everyone will have to play their part. Because unless that happens, the headlines we are seeing today will become much more dire and we will reach a point of no return.

- An international treaty expanding the agenda of being committed towards its parties in reducing the emissions of six greenhouse gases in 41 countries plus the European Union to 5.2 % below 1990 levels

- Adopted in 2015 was adopted with an aim to limit global warming to below 2°C and extended efforts to gradually limit it to 1.5°C and to strengthen the countries’ ability to deal with the adverse effects of climate change