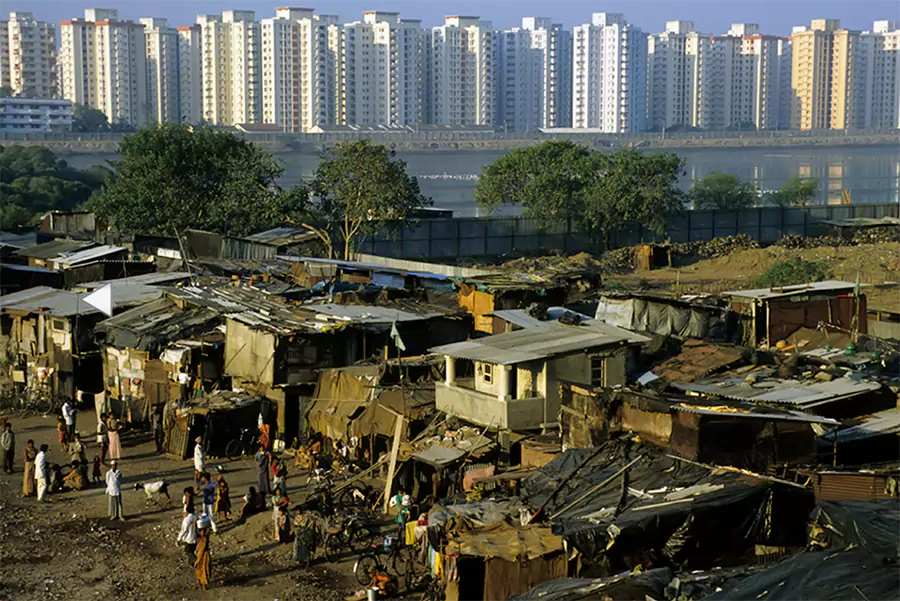

Persisting and increasing inequalities have been a defining feature of our times. French economist Thomas Picketty, in his seminal work Capital in the Twenty-First Century, has postulated that inequalities are here to stay as they are hardwired into the system. Returns to capital have been, and continue to be, much greater than those that are possible from labour. The rich have the capital, which keeps multiplying even while they are asleep, while the poor can rely only on their labour, which will never be enough to catch up.

In the face of these grim predictions, history provides some clues as to how certain events have reversed these seemingly inevitable trends and inequalities have been reduced. Large inequalities existed from the times of Pharaonic Egypt to the Roman empire, Mughal India and Victorian England. However, these inequalities did not continue to rise ad infinitum, but in fact were reduced. In his book The Great Leveler, historian Walter Scheidel has undertaken an extensive analysis of data from across several centuries and has identified four “horsemen” that have tended to reduce inequalities—wars that mobilised large populations, transformative revolutions, state failures, and pandemics.

Now the question is: will the current pandemic reduce current inequalities?

In my humble opinion, the answer is an emphatic no. The four “horsemen” reduced inequalities at some points in time during recorded history by providing violent shocks to the system and disrupting the established order. These shocks attenuated the powers of rulers, decimated the powerbase of the elites, and drove up the value of low-skilled workers. In the current pandemic, however, none of these factors seem to be in play. In some ways, it is the reverse that seems to be happening. The poor appear to have borne the brunt of the negative impacts of the pandemic while the rich have benefitted from the innovations and reforms spurred by the pandemic.

Instead of relying on the fourth “horseman”, namely the ongoing pandemic, for reducing inequalities, policy-makers should perhaps focus on at least four factors that are increasing inequalities. I refer to these as the four “Trojan horses,” as they are surreptitiously becoming a daily part of our lives and some of them are even needed for promoting prosperity. However, without us realising, they further deepen the wedge between the haves and have-nots.

The first “Trojan horse” is the macroeconomic situation world-wide, which is disproportionately penalising the poor and benefiting the rich. Faced with slowing economies in early 2020, central banks in all the major economies followed highly expansionary monetary policies, only recently starting to tighten them. This has led to asset price inflation, enriching those who had assets to begin with. For example, the Sensex was around 30,000 in mid-March 2020. Even after some correction in recent times, it stands at 52,000 today, having multiplied the wealth of those who own equity by around 60%. At the same time, all the major economies, including India, are facing decade-high levels of inflation, which disproportionately squeezes consumption by the poor. Addressing inflation without reducing the prospects for growth and employment will be an unenviable task for policy-makers.

The second critical policy issue or “Trojan horse” is the increasing inequalities in access to and quality of education, which have been exacerbated by the pandemic, deepening the chasm between children who have been able to continue their schooling over the past two years and those who have not. There is emerging evidence that the large proportion of children who dropped out during the pandemic are not likely to go back to school. The World Bank estimates that due to prolonged school closures and poor learning outcomes, “learning poverty” – that is, the share of 10 year-olds who cannot read a basic text—may have increased from 53% before the pandemic to 70% in low- and middle-income countries. These inequalities will have a lasting impact on the productive capacity and future earning potential of these children, as they join the labour force in the future. Thus, the consequences are likely to be with us for decades to come. How to bridge this large and increasing gap in learning outcomes is a second major challenge.

The third “Trojan horse” is jobs and the potentially increasing inequalities in the labour market. There have been concerns about the numbers and quality of new jobs being generated, with the employment elasticity of growth coming down and the number of so-called gig-economy workers with no job protection and social protection going up. Women’s labour force participation in India is at about 20%, one of the lowest among peer countries. The pandemic has also reinforced pre-existing inequalities in the labour market. During the lockdown phase, lower skilled workers predominantly in the informal sector, suffered heavily. Even though the poor could not afford to safely stay at home, they did not have anywhere to go, as roads, shops and workplaces closed. The pandemic also exacerbated gender-based inequities in income and employment. Evidence is emerging that women were the first to be fired when many companies down-sized. The new jobs that emerged due to the pandemic—such as an increase in the demand for delivery persons—primarily went to men. In addition, with the burden of additional work in homes required in the form of childcare, home schooling of children and domestic chores falling disproportionately on women, gender inequality in earnings is particularly likely to have grown even wider. How to create quality jobs, reduce inequalities in the labour market and increase women’s labour force participation will be a third major policy challenge.

The fourth “Trojan horse” for increasing inequalities, ironically, is something that has led to impressive growth and prosperity in the country—innovations in information and communication technology (ICT). In current times, access to, and the ability to work with, ICT significantly determines one’s ability to acquire skills, jobs and materials for daily needs, seek medical help through tele-medicine, conduct business, and even find a life partner. A large number of people on the other side of the digital divide are getting left behind and, at a much greater pace than possibly at any other time in history. The pandemic may have further widened these gaps. Changes in work patterns and innovations to facilitate working remotely have benefitted those who are educated and technology-savvy. Working from home has improved productivity for many by reducing their commute time and giving them more flexibility. However, for people relying on manual labour such as guards, messengers and construction workers, working arrangements have not changed at all. Aggressively bridging the “digital divide” and making ICT work for the poor and disadvantaged, including women, will need considerable effort.

We cannot rely on the “horseman” of the pandemic to flatten inequalities. As they say in all investment warnings, past performance is no guarantee of future results. We will have to chart our own path, guided by the new realities and evolving context. We will need to directly take on the four Trojan horses by controlling inflation, addressing education deprivation, creating quality jobs and making technological innovations work for the poor.