India has been in a serious water crisis for the past 20 years. Per capita availability has declined to about 1,400 cubic meters annually and will decline further as urban and industrial growth accelerates. The issues are well known, but in their thematic and administrative silos.

Will India’s water woes become worse? Most research seems to say Yes. By some estimates, the demand for water in India in 2030 will outstrip supply by almost 100%. While there are numerous schemes sponsored by the Central, State, and local government to either augment water supply, conserve water, recharge groundwater, rejuvenate water bodies, or invest in rainwater harvesting. All of them miss one key point: Efficiency.

Our agriculture sector takes 84% of total freshwater available estimated at 850 billion cubic meters (bcm), which is further estimated to increase to 1,072 bcm by 2050. This irrigates about 49% of all farmlands (140 million hectares). The 38% irrigation efficiency number has to improve dramatically. Nothing short of a revolution in farm hydraulics can help. Moving water to and around farms require ‘smart’ concepts. Water will have to be captured and stored locally; public irrigation systems have failed and are sub-optimal at the best of times. Atomistic irrigation will need to be the new norm. Digitized automation will be key as urban migration continues and farm labor shortages increase.

We use 25% of the world’s groundwater; 90% of it goes to agriculture. The groundwater ‘anarchy’ must be addressed by new technologies that reduce energy costs and align with micro irrigation systems. India’s use of micro irrigation is still miniscule – coverage is less than 8 million hectares. This must grow. Inefficiencies will persist if investments are not scaled up rapidly. Conveyance losses will decline by adopting new technologies in pumps, pipes, leakage control, and pressure management systems. Farmers need multiple crop options and water transport systems will have to respond. Finally, farm water quality will have to improve; irrigation run-off and drainage will take on whole new meanings. This is the revolution that needs to be engineered. We do not have time.

But do we have money? India’s agriculture is addicted to subsidies worth about $48 billion annually. While these subsidies are the stuff of politics, if even half this number is invested in reducing the water footprint of Indian agriculture, our water security would be assured without any impact on farm incomes or production volumes. Further, if we were to tackle food waste, currently at about 40% of total production, it would help materially in reducing our water bill.

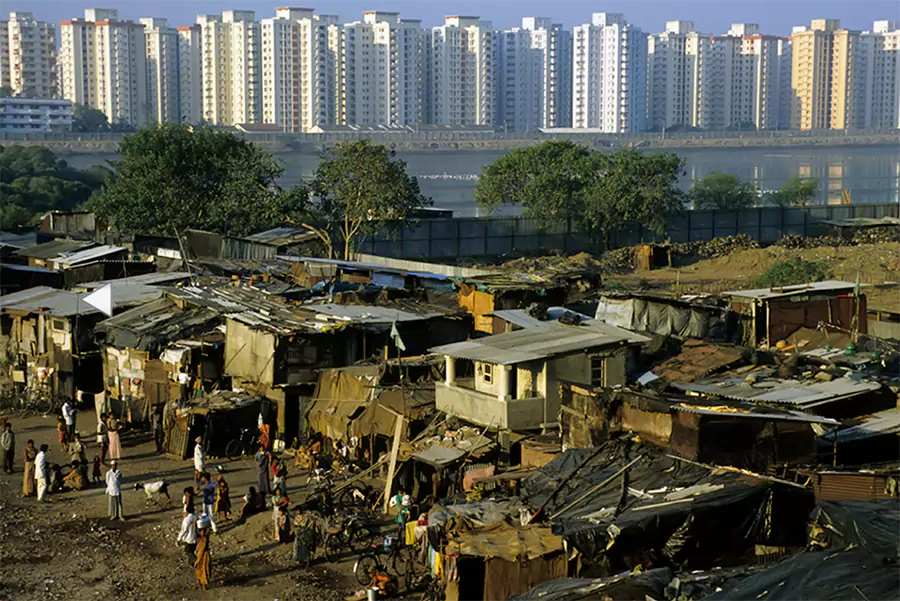

The municipal sector drew 56 bcm of water in 2010, a number that is expected to go to 102 bcm in 2050 premised mainly on urban and industrial growth. It will be virtually impossible to find new water of this magnitude given that our cities are already water short. Most of urban India loses between 40-70% of treated water. But investments are not focused on reducing nonrevenue water. Instead, investments go to new water sources, including those in already depleted groundwater fields. Because India’s public sanitation systems are generally poorly designed and septic tanks and sewer lines leak all the time, most clean water reticulation systems get polluted through seepage. Quite apart from the estimated 200,000 deaths annually on account of water-borne disease, the burden on public health systems is economically wasteful.

Local governments need to have only one genre of projects over the next 15 years: reducing nonrevenue water. Cities like Manila and Phnom Penh have done so. It is not difficult. Nor is it half as expensive as new source development. The saved water will not only service those who are currently unserved but will also generate revenues. At the same time India’s cities need to go down the circular economy path. All raw sewage and septic tank discharge must be treated by standards that allow reuse by a variety of markets. Peri-urban agriculture is already a market for treated wastewater; so are power plants and industries that are victims of inadequate or unpredictable water supplies.

It is true that efficiency in water supplies, or the development of a circular water economy, will not be optimized without the right institutional arrangements. But we cannot wait for India to rationalize its highly fragmented water world and create unified systems where public utility and consumer interests are regulated independently, and where the costs of providing an efficient service are recovered. Let us note that ‘free’ water to consumers is a false concept and has not worked anywhere. Likewise, the mantra that says “lets fix the institutions first; they will take care of the pipes” is delusional, certainly in the Indian milieu. Making perfect the enemy of the good will not help. No further time should be lost in reducing India’s staggering nonrevenue water. There cannot be any other higher priority if social equity and sustained economic growth is to be ensured.

In the Energy sector, India needs to accelerate its move to renewable sources that are not water dependent. Currently, about 30 bcm are drawn annually, of which 6 bcm are consumed. Clearly, high-cost thermal and hydropower systems cannot be given up in the near term, but they must be upgraded to maximize water use efficiency. Where new plants are being built, the latest technologies must be adopted, and sustainable water linkages established in areas that are either water surplus, or water neutral. It makes little sense to lose 14 terawatt hours of power generation as we did in 2016.

Efficiency of water use in Industry continues to be an issue. Growth in demand is expected to rise from 10 bcm in 2010, to 23 in 2025, and 63 in 2050. The problem is twofold. Consumption is not premised on efficient use and wastewater is not treated. Far from being available, after treatment, as new water, industrial effluent contributes to widespread freshwater pollution. India needs to rapidly establish an industrial water standards regulator with prescriptions for consumption per product output.

So, to the question: have we gone past our tipping point? We probably have. Demand is already close to accessible supply. Climate change does not help. A well-known adage is: If climate change is the shark, water is its teeth. Extended and unpredictable dry seasons, together with unseasonal, and extreme precipitation, make water management doubly challenging. In these circumstances, it makes political and economic sense to use our available freshwater efficiently. This is not the time to endlessly debate institutional reforms, or water budgets. It is high time we got Efficient.