India stands on the brink of a massive opportunity. Quality education and health for the 26 million children born each year and the 65 per cent of the population under the age of 35 could help provide a workforce that would propel India forward.

India is one of the few middle-income countries with a growing working-age population. It can harness this demographic dividend and potentially become a developed country within a generation. However, the window of opportunity is narrow and urgent actions are needed to achieve this goal.

In her 2023-24 Union Budget speech, the finance minister announced that the total central government budget for health (not including research) will be roughly Rs 86,175 crore ($10 billion) — that is, roughly Rs 615 for every citizen. This is a 2.7 per cent increase from the previous fiscal year and lower than the rate of inflation.

In real terms, the central government’s health spending has declined. Vaccinating a single child against all childhood illnesses costs at least Rs 1,600.

A day of hospitalisation at a public hospital is estimated at Rs 2,800. At a private hospital, it is Rs 6,800. Add to these the expenses for supporting women through deliveries, control of infectious disease, primary healthcare, and much more, and the Ministry of Health is being asked to carry out a heroic effort on a shoestring. It is, therefore, no surprise that the system fails the most vulnerable and they are forced to turn to the expensive private sector.

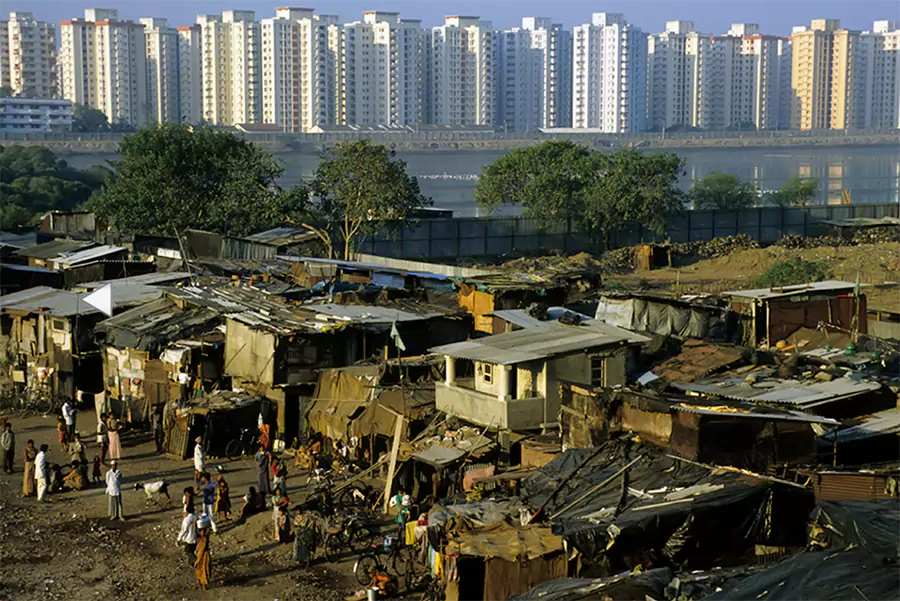

The poor, elderly and sick are already at a disadvantage and the burden of health expenditure makes this even worse.

A greater proportion of disposable incomes is taken away from a poor household as compared to a non-poor one, further broadening the gap between the two. If sickness hits a working member of the household, she/he must often withdraw from active employment and their main source of income dries up at the time when they urgently need more money for treatment.

Households have to often sell or mortgage their productive assets, such as land and cattle, to cover the treatment costs.

This further reduces their capacity to bounce back. According to the WHO, 55 million people fall into poverty or deeper poverty every year due to catastrophic expenditures on health.

India currently spends about Rs 8 lakh crore ($100 billion) or about 3.2 per cent of its GDP on health. This is much lower than the average health spending share of the GDP — at around 5.2 per cent — of the Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMIC).

Of this, the government (Centre and states put together) spends about Rs 2.8 lakh crore (about $35 billion) — roughly 1.1 per cent of the GDP. Contrast this with the government health expenditure in countries like China (3 per cent), Thailand (2.7 per cent), Vietnam (2.7 per cent) and Sri Lanka (1.4 per cent).

This is not a matter of efficient use of resources — when the country spends too little on health, too many people suffer the consequences of ill health.

The $10 billion spent by the central government may be a small fraction of overall health spending but it is consequential as it pays for immunisation, newborn and child health and nutrition, maternal health, infectious disease control, health systems and training. Rupee for rupee, this spending by the government purchases far more health than out-of-pocket or private spending by Indian citizens.

We highlight three areas where greater spending by the central government could help in the immediate term.

First, the National Health Mission allocates less than 3 per cent (Rs 717 crore) to non-communicable diseases (NCD) flexipool. In comparison, the allocation for communicable diseases is three times more at Rs 2,178 crore and for reproductive and child health services about nine times greater at Rs 6,273 crore.

The burden of disease from NCDs accounts for more than half of the total burden of disease and this proportion further increases in both rural as well as urban areas. Greater focus on communicable diseases is driven by past epidemiological patterns and should be rebalanced now to pay attention to non-communicable diseases.

Second, public health and primary health care focus on rural areas. Urban areas have poorly developed infrastructure for primary care even if secondary and tertiary health care services are better. For example, immunisation coverage is now lower in urban India than in rural India. A third of the country now lives in urban areas and greater resources are needed to improve health here.

Third, health research has been neglected for too long. The allocation for the Department of Health Research in this year’s budget is Rs 2,980 crore, flat from last year. Spending Rs 20 per Indian is inconsistent with the need for innovations and technologies in the sector. The bulk of the resources provided to the Indian Council of Medical Research goes towards maintaining a large payroll of scientists and the output is poor.

India should follow the example of countries where government-funded health research is conducted at academic institutions, and the government’s role is to make grants — not to carry out the majority of research. Competitive funding will encourage the best research and the example of the Welcome Trust/DBT-India Alliance in promoting the culture of competitive grants can be replicated across the system.

The health (and education) of Indians is the most important determinant of what the country can achieve during the next 25 years of Amrit Kaal. We must find ways to both find more money for health, and also more health for the money to ensure that all Indians achieve their true potntial.