We need an urgent and well-resourced ‘whole-of-society’ approach to protecting, promoting and caring for the mental health of our people.

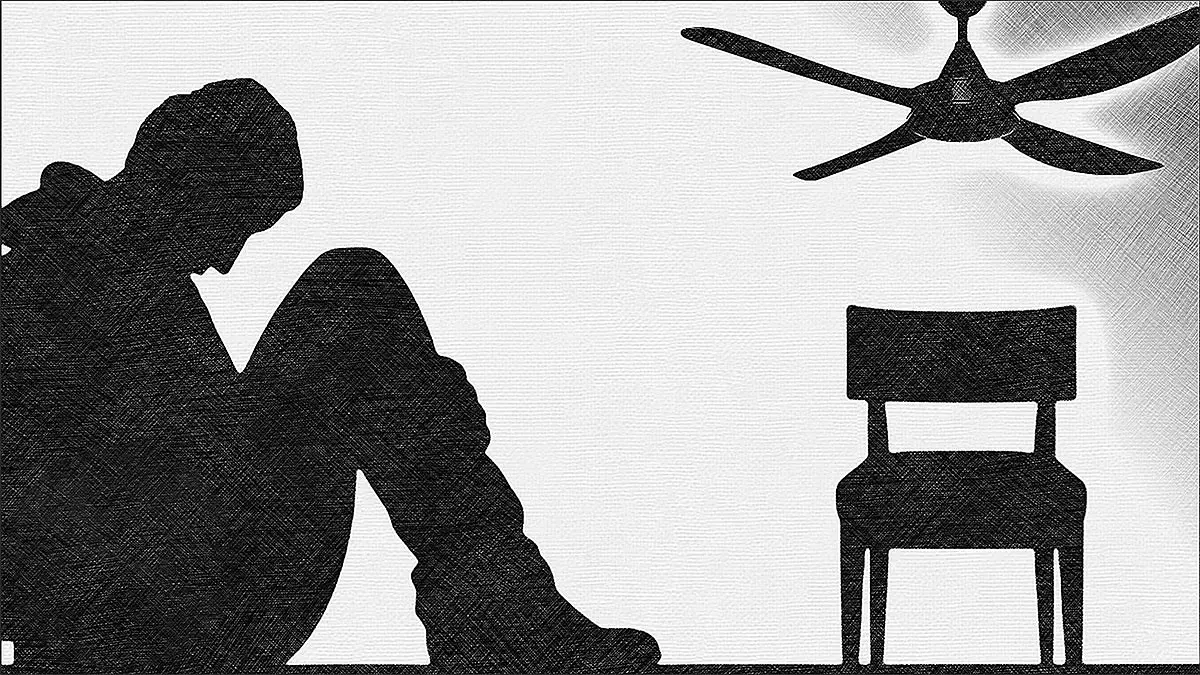

Every other day, we wake up to a disturbing headline of a young person having left us by committing suicide. Suicides rates in India are amongst the highest when compared to other countries at the same socio-economic level. According to WHO, India’s suicide rate in 2019, at 12.9/1,00,000, was higher than the regional average of 10.2 and the global average of 9.0. Suicide has become the leading cause of death among those aged 15–29 in India.

While every precious life lost through suicide is one too many, it represents only the tip of the mental health iceberg in the country, particularly among young adults. Women tend to suffer more. Across the world, the prevalence of some mental health disorders is consistently higher among women as compared to men.

The pandemic has further exacerbated the problem. Globally, it might have increased the prevalence of depression by 28 per cent and anxiety by 26 per cent in just one year between 2020 and 2021, according to a study published in Lancet. Again, the large increases have been noted among younger age groups, stemming from uncertainty and fear about the virus, financial and job losses, grief, increased childcare burdens, in addition to school closures and social isolation.

Increased use of certain kinds of social media is also exacerbating stress and mental ill health for young people. Social media detracts from face-to-face relationships, which are healthier, and reduces investment in meaningful activities. More importantly, it erodes self-esteem through unfavourable social comparison.

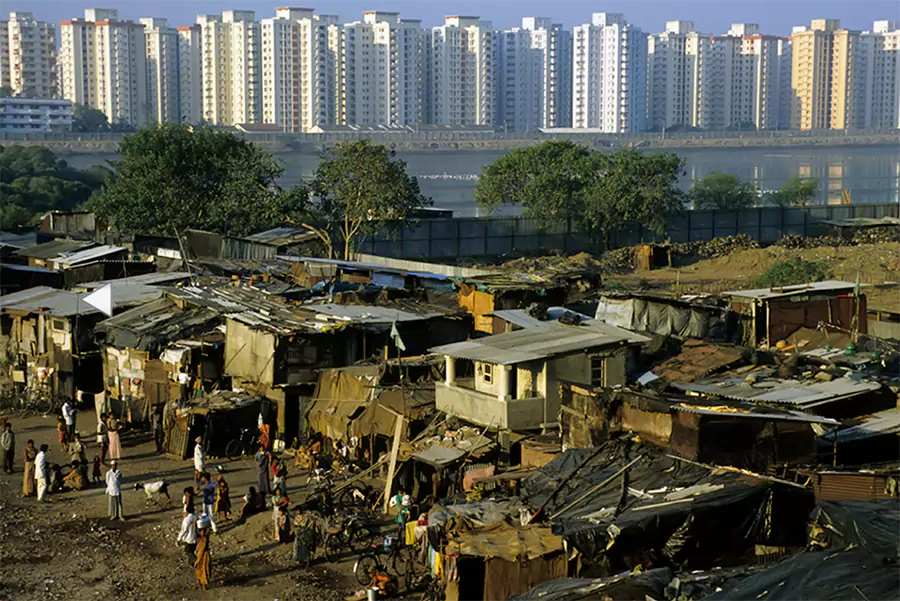

Mental ill-health has larger socio-economic implications. It is a leading cause of disability globally and is closely linked to poverty in a vicious cycle of disadvantage. People living in poverty are at greater risk of experiencing mental health conditions. On the other hand, people experiencing severe mental health conditions are more likely to fall into poverty through loss of employment and increased health expenditure. Stigma and discrimination often further undermine their social support structures. This reinforces the vicious cycle of poverty and mental ill-health. Not surprisingly, countries with greater income inequalities and social polarisation have been found to have a higher prevalence of mental ill-health.

We need an urgent and well-resourced “whole-of-society” approach to protecting, promoting and caring for the mental health of our people, like we did for the Covid pandemic. This should be based on the following four pillars.

The first pillar should be killing the deep stigma surrounding mental health issues which prevents patients from seeking timely treatment and makes them feel shameful, isolated and weak. Actor Deepika Padukone is a role model that other public personalities with mental health issues need to follow to show how they can lead productive lives. Recently, I proudly watched my daughter Devika Bhushan, who was acting surgeon general of the California state in the US at the time, share her own struggles with mental health issues in a large conference in order to encourage others to break free of internalised shame and reluctance to seek treatment. She said, “Stigma festers in the dark and scatters in the light.” We need a mission to cut through this darkness and shine a light on the fact that most mental health conditions are very treatable. With treatments in place, you can live a full life.

The second pillar is making mental health an integral part of the public health programme to reduce stress, promote a healthy lifestyle, screen and identify high-risk groups and strengthen mental health interventions like counselling services. Special emphasis will need to be given to schools. In addition, we should pay special attention to groups that are highly vulnerable to mental health issues such as victims of domestic or sexual violence, unemployed youth, marginal farmers, armed forces personnel and personnel working under difficult conditions.

The third pillar is creating a strong infrastructure for mental health care and treatment. Lack of effective treatment and stigma feed into each other. Currently, only 20-30 per cent of people with mental illnesses receive adequate treatment. One major reason for such a wide treatment gap is the problem of inadequate resources. Less than two per cent of the government health budget, which itself is the lowest among all G20 countries, is devoted to mental health issues. There is a severe shortage of mental health professionals, with the number of psychiatrists in the country being less than those in New York City, according to one estimate. The Director General of one Central Armed Police Force told me that he has only two mental health specialists for a 3,00,000-strong workforce. Substantial investments will be needed to address the gaps in the mental health infrastructure and human resources.

Finally, mental health services should be made affordable for all. Improved coverage without corresponding financial protection will lead to inequitable service uptake and outcomes. All government health assurance schemes, including Ayushman Bharat, should cover the widest possible range of mental health conditions. Currently, most private health insurance covers only a restricted number of mental health conditions. Similarly, the list of essential medicines includes only a limited number of WHO-prescribed mental health medications. A comprehensive review of these policies will be needed to ensure that financial and other barriers do not prevent people from using services or push them into poverty.

Brock Chisholm, the first Director General of WHO, famously said, “there is no health without mental health”. More than 50 years later, as we strive to provide universal health coverage to our population, let us ensure that mental health is an integral part of our approach.